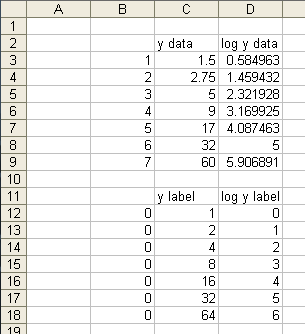

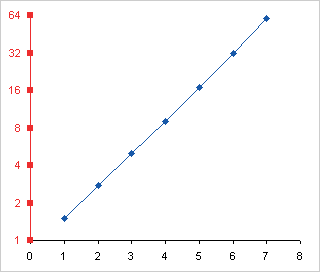

In Custom Axis, Y = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 I showed axes with base 2 logarithmic scales in both Excel 2003 and 2007. In Excel 2003 it is necessary to transform the data to get the intended result. In Excel 2007, the axis can be achieved with the untransformed data.

In the previous post, the data was widely spaced, so it filled a base 10 log scale with two decades with only a reasonable amount of space above and below the data.

If the data isn’t spread out so nicely, you lose the opportunity to use a regular logarithmic axis. We’ll look at this for Excel 2003 and for Excel 2007, and then we’ll look at native logarithmic axis labeling.

Excel 2003

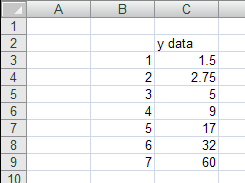

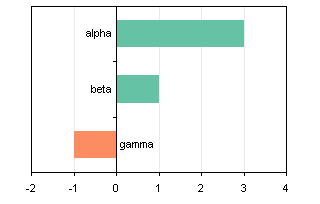

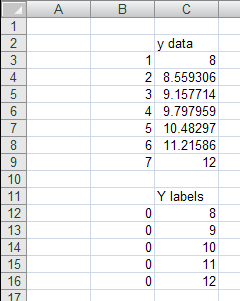

The data in the table below has a narrow range, from 8 to 12, and the range spans a power of ten.

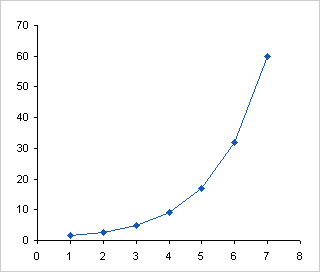

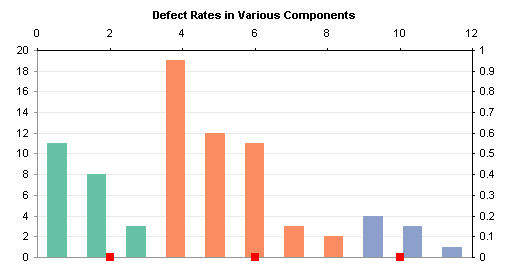

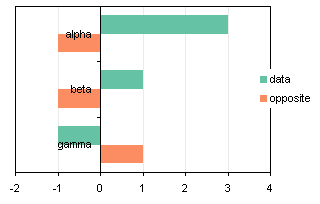

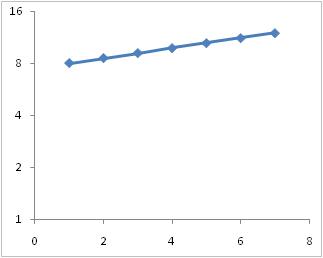

Here is the data charted using a linear axis.

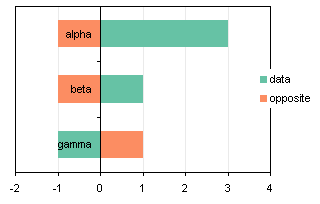

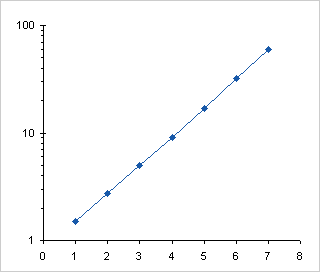

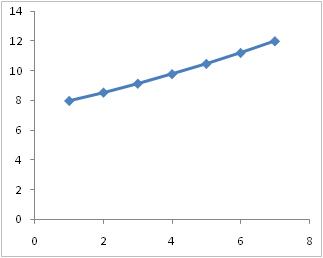

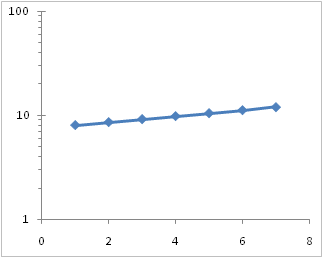

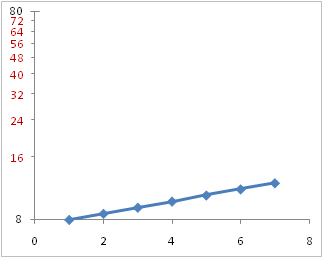

When we apply a logarithmic scale axis, the data spans across 10, so by default the axis ranges from 1 to 100. The data is squeezed into the middle of the chart.

Since Excel 2003 only permits the axis to begin and end at powers of ten, we’re stuck with this, and the fanciest labeling doesn’t make the data easier to read.

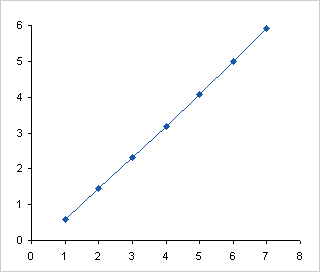

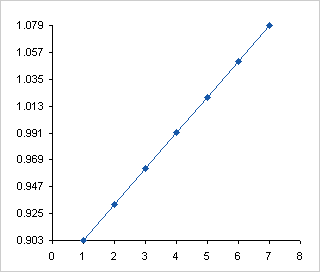

Following the steps in Custom Axis, Y = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 we can plot the logs of the data on a linear scale, from log(8) = 0.903 to log(12) = 1.079.

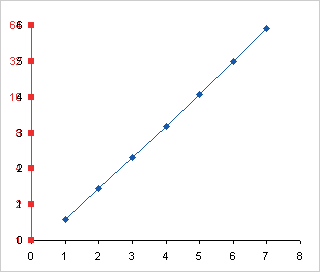

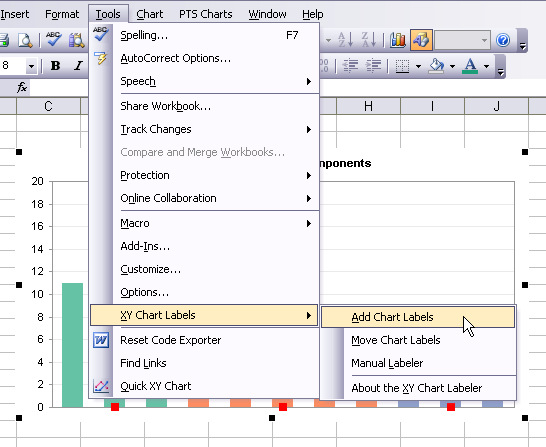

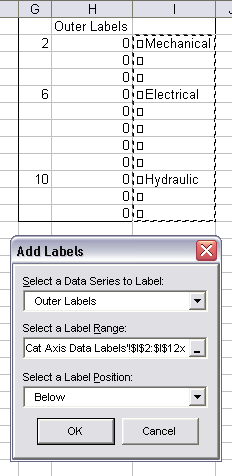

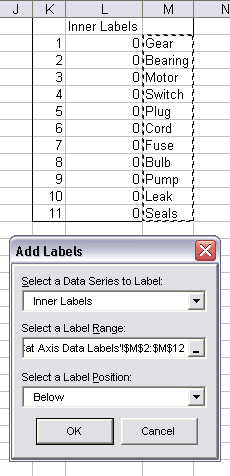

We can hide the default labels, add a series with points where we want our custom labels using log(Y) data, and use the Y values as data labels.

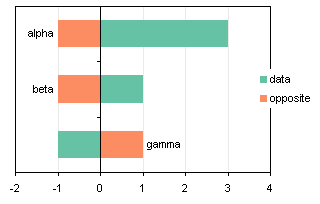

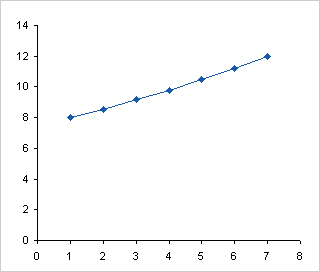

Here’s the chart. With such a narrow spread in the data, it’s not immediately apparent that the Y scale isn’t linear, but if you took out your ruler (you still have one of those, right? you’re not completely digital?) you can tell that the span between 8 and 9 is larger than that between 11 and 12.

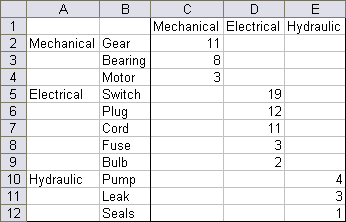

Excel 2007

As described in Custom Axis, Y = 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, Excel 2007 makes working with log scales a bit easier.

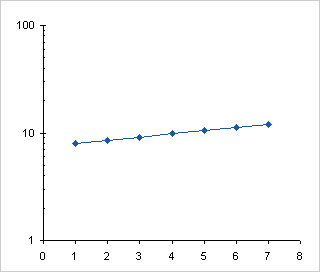

Here is the data plotted on a linear scale.

Here is the same chart, with the scale transformed to a logarithmic scale, using the default base 10. Same as Excel 2003.

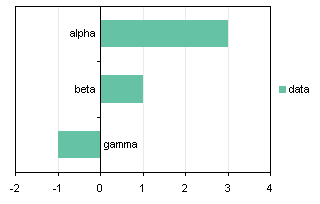

Here the log scale has been changed to base 2.

In 2007 we can change the min and max of the log axis to values other than 10 (i.e., other than the base). Here the axis ranges from 8 to 80, still a decade on the base 10 log scale. Instead of the minor ticks being located at multiples of ten (20, 30, 40, 50,…), they are located at multiples of 8 (16, 24, 32, 40,…)

We can also change the maximum so that the axis spans a non-integral number of cycles. Here the maximum is 12 to fit the data. This looks the same using base 10 or base 2.

We don’t get labels other than at the minimum because the axis spans less than a power of base 10 or of base 2, but we can use the same protocol as above to add points with data labels. The advantage Excel 2007 has over 2003 is that we can use the actual values to locate the points, and we can simply use the Y value data label option. In Excel 2003 we had to use the log of the Y positions, and either manually edit the labels, or use a third-party add-in. (Even though the add-in is great, it still is something extra required.)

Finished. Again, just like Excel 2003, only easier.

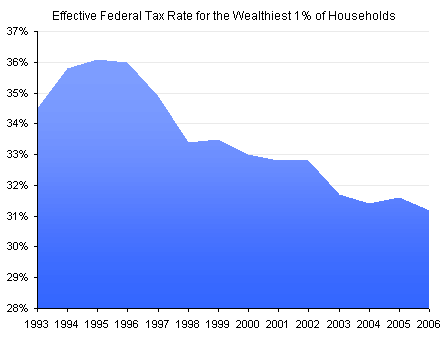

Log Axis Labeling

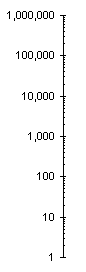

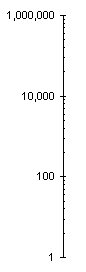

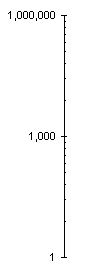

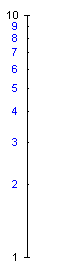

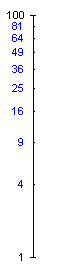

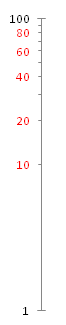

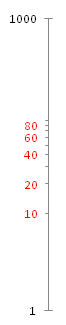

Below are a few variations on a log axis that spans six cycles. These were produced in Excel 2003, but they would be the same in 2007. The scales show both major and minor tick marks, which are available for any base except for 2.

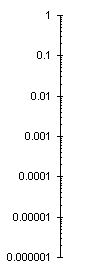

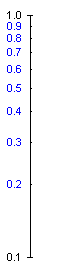

The first scale runs from 1 to 1,000,000, and the second from 1/1,000,000 to 1. The third and fourth run from 1 to 1,000,000 like the first, but instead of the default major unit (major tick spacing) of 10, the third has a major unit of 100 and the fourth of 1000. The minor tick spacing is ignored.

If you use the default major unit, minor ticks are placed at multiples of the number at the start of the cycle. In the Excel 2007 chart above that used a base 10 log scale and ranged from 8 to 80, the minor ticks were at multiples of 8 (16, 24, 32, 40,…). In our first axis below, the bottom of the decade is at 1, so minor ticks are at multiples of 1 (2, 3, 4, 5,…). The the second axis, the bottom of the decade is at 0.1, so minor ticks are at 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and so forth.

In 2003, when the non-default major unit is used, the space between major tick marks is divided up as if it were a single cycle (not two or three. Instead of the ticks being located at 2, 3, 4, etc, for a major unit of two cycles, the minor ticks are located at the square of the one-cycle values, that is, at 4, 9, 16, etc. For a major unit of three cycles, the minor ticks are located at the cube of the one-cycle values, that is, at 8, 27, 64, etc. Interesting.

Excel 2007 does this a bit differently, and for a two-cycle major unit, it makes sense. The first pair of axes below show a scale of 1 to 100, first with the major unit defined by the default one cycle, then by two cycles. I’ve added labels to many of the minor ticks to help illustrate this behavior. The two cycle axis has the first minor tick where the first cycle ends and the next cycle starts, then the rest of the ticks are where they were defined for the second cycle. This puts the ticks at the very logical values of 10, 20, 30, etc.

With larger spans between major ticks, Excel 2007 seems to get confused. The second pair of axes shows three cycles with major units of one and three cycles. The three-cycle axis places minor ticks where the two-axis tick did in the first instance, at multiples of 10 between 10 and 90. There is no tick at 100, nor any between 100 and 1000. Not shown is a four-cycle axis. This puts minor ticks at multiples of 10 between 10 and 90, and at multiples of 1000 between 1000 and 9000, but skips the decade between 100 and 1000.

– – –

– – –

This is pretty obscure. It doesn’t make sense to use multiple cycles as the major unit. In a two-cycle major unit, Excel 2007 uses more logical minor tick spacing, while the minor tick spacing is broken for larger major units. Excel 2003 uses a consistent minor tick spacing which is logical in its own way, but not readily understandable.