There has been a lot of discussion about pie charts and bar charts lately. I and many other know-it-alls have clearly stated that pie charts are the red-headed stepchildren in the family of chart types. In Peltier Loves Pie I provided some guidelines to follow if you still insist on using pie charts.

In this post I am giving bar charts equal time.

Bar Charts

Bar charts are widely used, and in most cases they present an improvement over pie charts. According to William Cleveland, the effectiveness of different human visualization skills are ranked as follows:

- Position along a common scale

- Position along identical unaligned scales

- Length

- Angle or slope

- Area

- Volumn

- Color

A bar chart relies on the lengths of its bars to convey information. Length is found higher than a pie chart’s angles or areas in Cleveland’s hierarchy of human perception, so bar charts are better than pie charts for presenting data. A bar chart also uses the same color for each point, so there should not be any unintended weighting of values by color.

Guidelines for Bar Charts

- Use horizontal bar charts so there is room for horizontal category labels.

- It usually helps to sort data so longer bars are at the top (or taller bars are to the left, if you use a vertical column chart).

- Use 2D bar charts only.

- Don’t use shadows, fill gradients, glows, or other distracting effects.

- Use zero as the baseline for the value axis, so the total lengths of the bars are visible.

- Avoid stacked bar charts, because bars which are not in the first layer do not have a common baseline.

- Avoid clustering more than about three or four series of bars.

- Don’t use bar charts for time series data.

Example Bar Charts

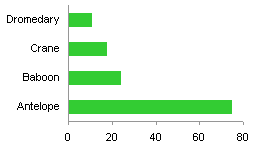

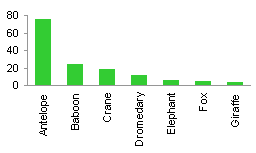

Here is the bar chart corresponding to the first pie chart in Peltier Loves Pie. Note that in a horizontal bar chart the value (Y) axis is the horizontal axis, and the category (X) axis is the vertical axis.

The bars are sorted smallest to largest, so format the category (X) axis scale so the categories are plotted in reverse order.

The value (Y) axis moved to the top, since it is still at the minimum (i.e., first) category. Format the category (X) axis scale again, so the value (Y) axis crosses at the maximum (i.e., last) category. (With experience you’ll remember to change both scale parameters at once.)

At first, the order of the bars may seem counterintuitive. They are listed in the sheet from largest to smallest, right? Well, the first item listed in the sheet becomes the first category, so it is closest to the origin (where the two axes cross). The second item becomes the second category, so it is plotted one slot further from the origin, which is higher on the vertical category axis.

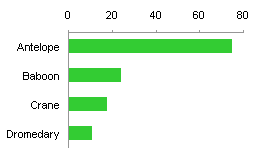

When points are added, the new bars are lined up parallel to the existing bars, and there is no impingement of adjacent labels as in the pie chart. Even if the data were not sorted, you could tell their relative values by their lengths. This would have been more difficult, even impossible, in the pie chart.

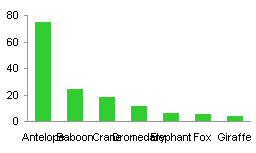

I recommended a horizontal bar chart, because a vertical column chart will have overlapping labels.

You could rotate the labels, which prevents overlapping, but requires more space for the label, and forces the reader to rotate his head to read the text.

Rotating to 45° seems like a good alternative, but it is not really much better than the vertical labels.

The best option is to stick to horizontal bars. This chart has all eleven points that the last pie chart had. The chart is not as large as the pie chart, and its labels are aligned with its points (the bars) without any interference between adjacent labels.

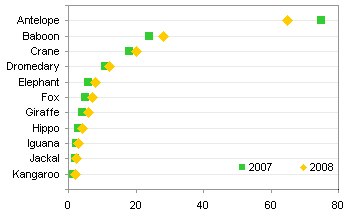

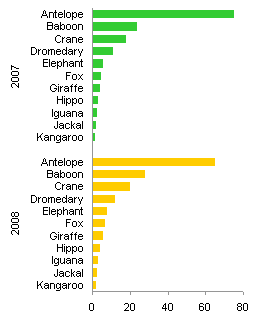

What about adding a series? Easy enough in a clustered bar (or column) chart.

Two or three clustered bars would be fine, but more than that would be too cluttered to be legible. You could rearrange the data to produce an alternate arrangement, but that may not be as useful for this particular data.

An alternative to a clustered bar chart for this display is a dot plot.