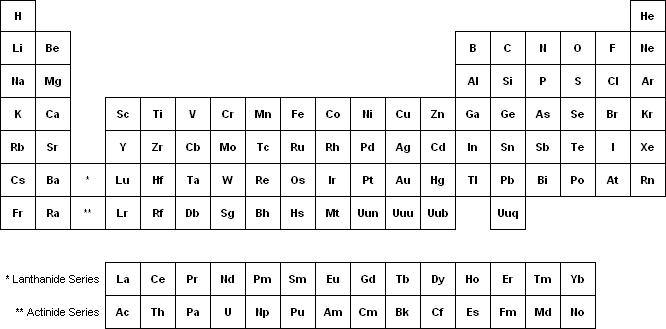

Periodic Table of the Elements

I remember in high school, and again in college, learning about the periodic table of the chemical elements.

Image of Periodic Table of the Elements from Elements Database removed at their request. The image above was created in Excel by me, so it falls under the Creative Commons license of this blog.

Russian chemistry professor Dmitri Mendeleev is credited with creating the first periodic table in 1869. He laid out the elements by atomic weight, and started a new row when the chemical properties of the elements began to repeat. Mendeleev had the foresight to leave gaps in his table where he suspected an as-yet undiscovered element should be, and he even had the temerity to make predictions about the properties of the missing elements. He occasionally switched adjacent elements if the properties did not correspond exactly to the atomic weights.

Long after Mendeleev’s time, scientists unraveled the secrets of the atomic and electronic structure of matter. It was learned that Mendeleev’s switching of some adjacent pairs of elements actually placed them in the correct atomic number sequence, defined by the number of electrons or protons in the unionized elements. The groups (columns) in the table are characterized by elements with the same valence electron structure, and thus, similar chemical properties.

The periodic table of the elements is an elegant and useful display, which arranges the elements by similar structure and properties,with characteristics changing predictably with changing rows or columns. There are sections for alkali metals, transition metals, rare earth metals, metalloids, nonmetals, and inert gases. In recent years, dozens of less periodic arrangements of objects have been forced into this format, despite the metaphor’s poor fit for most of them.

Periodic Tables of Whatever

One of the most popular is the Periodic Table of Visualization Methods. This is the faux periodic table that has led me to despise the genre. It’s about visualization, yet it’s visually unattractive. Mostly it seems that they had a set of boxes and a list of visualization methods, and pigeonholed the one into the other until they were done. And some of the examples they show (when you mouse over the “elements”) are only worthy of USA Today.

The Periodic table of awesoments is amusing. Some thought went into this PT of X. I liked Group 2 (IIA) as well as the faux metalloids, the IIIA-VIA metals, and the Rare Earths. The rest seemed to be a struggle to think of enough other elements to fill the TMs, Halides, Halogens, and Noble Gases. Perhaps I don’t share enough obscure obsessions with the author.

Most of the PT of X attempts suffer from trying to hard to force an inappropriate metaphor. And when the metaphor fits poorly, the PT of X still tries to fit into the exact same periodicity as that of the electronic shell structures of the real elements (i.e., 2-6-10-14). As a result, most are just lame grids.

You can find an amusing Table of Condiments That Periodically Go Bad, a Periodic Chart of Beer which is really no more than a list (Coors light next to Heineken next to Foster’s??), a Periodic Table of the Presidents which is simply a listing of presidents in chronological order (not by policies), a Periodic Table of Languages which lists languages in alphabetic order (not by linguistic properties), a Periodic Table of the Internet [link no longer available] which shows no particular rhyme or reason to its organization, even a Periodic Table of Sex, which is the final proof that the wrong metaphor makes anything not fun.

One of the most creative and descriptive non-chemical periodic tables I’ve ever seen was of musical instruments, done several years ago by a former classmate of my daughter. There was a progression in size from top to bottom (e.g., violin, viola, cello, bass), which is sensible for instruments as well as for atomic elements. The groups were separated into morphologies, with strings over here, woodwinds there, the brass section, and percussion. The “Rare Earth” section was a rehash of the above instruments which had been electrified. Aside from the Rare Earths, there was no attempt to force a fit between this arbitrary X and the chemical elements. And it was an appropriate project for a seventh-grader.