Guest post by Zack Barresse & Kevin Jones

Data Automation Professionals, LLC

Zack and Kevin are VBA ninjas who have been helping people around the internet for several years. They’ve combined resources and started a company, Data Automation Professionals, which helps Excel users automate simple to complex tasks, consults on projects, and teaches the world VBA. Zack has been hanging around forums like Mr Excel and VBA Express for several years, and maintains the blog at exceltables.com. Kevin is an engineer who has been spotted around the net using the online moniker ‘zorvek’. Together they’ve written a book on Excel Tables: A Complete Guide for Creating, Using and Automating Lists and Tables

.

With the introduction of Tables in Excel 2007 (Tables are a re-invention of Lists, introduced in Excel 2003), we were also provided a new syntax for referencing Tables and the parts within those Tables. This new syntax is called structured referencing. The reason a new referencing method is required is because Tables are very dynamic, and the traditional cell referencing syntax would not allow robust referencing without clever use of functions as Tables as data is added and removed. As you will see in this article, structured referencing is a very powerful tool that makes your formulas dynamic while maintaining significant simplicity. If you’re not familiar with Tables, a good starting point is this blog post (with video) by Excel MVP Jon Acampora.

Tables play an integral part of modern Excel. They’re very organized, controlled, and most importantly, they have rules. These allow for a lot of built-in functionality previously unavailable. Functionality such as good data structuring, dynamic chart ranges, dynamic PivotTable sources, etc. Additionally there is some default behavior which can be nice such as banded rows and columns, cell formatting that is added to every new row of a table, and new rows auto-populating with formulas.

All examples in this article are for Excel 2010 and later. There is a slight difference between using structured referencing in Excel 2010 and Excel 2007—Excel 2007 is not covered in this article. For the purposes of discussion, the traditional method of referencing cells (i.e. A1, A2, B1:B100, A2:D100, etc.) is referred to as standard referencing.

Structured Referencing

Before we get too in-depth here, let’s make sure we have a good understanding of what is meant by structured referencing. Structured referencing makes it easier and more intuitive to work with cell references in Tables. It allows you to reference a Table’s parts such as the columns, header rows, and total rows without using standard referencing (R1C1 or A1 syntax) but rather by using the Table’s name and other constants such as column header values which makes references easier to read because recognizable names are used. This eliminates the need to use complex formulas or rewrite formulas when the Table structure is changed or data is added or removed. Formula audits are also made much easier.

Let’s look at a quick example of referencing the hours, let’s say this is stored in column A, and the rate, stored in column B. The standard referencing formula to calculate the total billable amount in row 2 is:

=A2*B2The structured referencing formula in row 2 (and in all other rows) is:

=[@Hours]*[@Rate]As you can see, with structured referencing it is much clearer what the formula is doing than with standard referencing. With standard referencing, we have to navigate to the source to determine what, exactly, is in cell A2 and B2. With structured referencing, we have greater transparency with makes development, maintenance, and auditing easier. In today’s world of Excel, with groups like EuSpRIG and heightened auditing and maintenance requirements, transparency in spreadsheets is as important as it’s ever been, and structured referencing goes a long ways to assist.

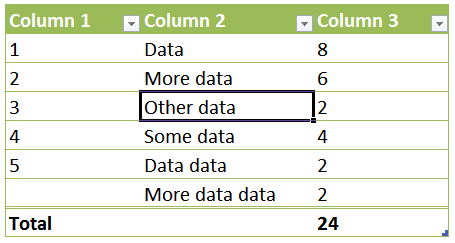

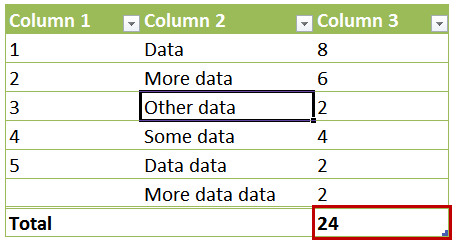

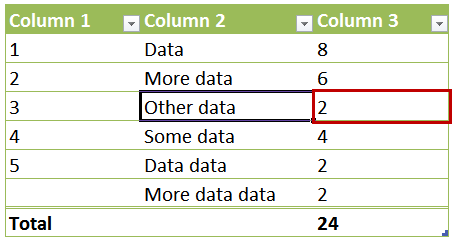

In the examples below, we will look at a simple Table which has three columns and six rows, with both the header and total rows showing. The image below is used for the next examples.

Before we get too in-depth on how the referencing actually takes place, there are a few rules to structured referencing which must be identified. In any single structured reference you may have a

- Table name,

- special identifier, or

- column name.

Generally only the column name is required, but every structured reference will have some combination of these three elements. Below are the basic rules of when to use these elements.

- The Table name used if

- more than one column of a Table is being referenced, or

- the column is being referenced from outside of the Table.

- A special identifier is used if a specific part of the Table is being referenced, i.e. the total row.

A key part of structured referencing is the use of square brackets. Square brackets are used to identify a reference as a structured reference versus a standard reference. Every structured reference (except the Table name itself) is enclosed in a set of square brackets. There are two occasions where you will have an additional set of square brackets.

Single-column cell reference

Column name of “Column” (no quotes used as the cell value) has a reference of:

[@Column]Column name of “A Column” (no quotes used as the cell value—note the space) has a reference of:

[@[A Column]]Multi-column cell reference

TableName[@[Column1]:[Column2]]In a multiple column reference, Excel will automatically place a separate set of square brackets around each column name regardless of whether or not there is a space or other special character in the name, as well as append the Table name to the reference. This is to identify it as an individual column within a multiple column reference.

Additionally, below are the characters which Excel identifies and automatically puts an additional set of square brackets around.

- Space ( )

- Line feed

- Carriage return

- Comma ( , )

- Colon ( : )

- Period ( . )

- Left bracket ( [ )

- Right bracket ( ] )

- Pound sign ( # )

- Single quotation mark (apostrophe) ( ‘ )

- Quotation mark ( )

- Left curly bracket (brace) ( { )

- Right curly bracket (brace) ( } )

- Dollar sign ( $ )

- Caret ( ^ )

- Ampersand ( & )

- Asterisk ( * )

- Plus sign ( + )

- Minus sign ( – )

- Equal sign ( = )

- Greater than ( > )

- Less than ( < )

- Division ( / )

This Row

The ampersand character (@) is used to identify “This Row” in a structured reference. This is also known as the implicit intersection of the row in which the reference resides.

Special Characters

Excel uses special characters to qualify structured references (discussed later in more detail) and, when these characters are included as part of a column name, they need to be “escaped” so that Excel does not interpret it as a special reference qualifier. The apostrophe ( ‘ ) is used for this escaping.

Below is a list of all special characters used to qualify structured references and must be preceded by an apostrophe when part of a column header.

- Left bracket ( [ )

- Right bracket ( ] )

- Pound sign ( # )

- Single quotation mark (apostrophe) ( ‘ )

- At sign ( @ )

Special Identifiers

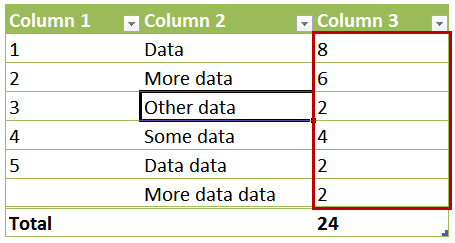

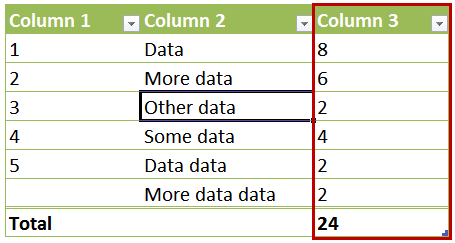

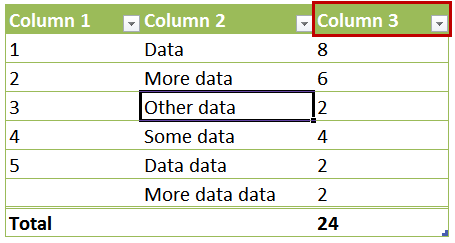

When attempting to reference specific parts of a Table, you will need to use a special identifier. There are only five. Let’s take a look at each of them and a picture for visual reference. In the following examples the referenced area is outlined with a red box.

[#All]

![Table Special Identifier [#All]](https://peltiertech.com/images/2015-06/SI_All.png)

[#Headers]

![Table Special Identifier [#Headers]](https://peltiertech.com/images/2015-06/SI_Headers.png)

[#Data]

![Table Special Identifier [#Data]](https://peltiertech.com/images/2015-06/SI_Body.png)

[#Totals]

![Table Special Identifier [#Totals]](https://peltiertech.com/images/2015-06/SI_Totals.png)

@ (or [#This Row] in Excel 2007)

![Table Special Identifier @ or [#This Row]](https://peltiertech.com/images/2015-06/SI_ThisRow.png)

Note that when referencing Table parts which are not visible or enabled such as when a header or total row isn’t showing, the reference will evaluate to a reference error (#REF!). Let’s look at an example formula:

=TableName[[#Headers],[Column 3]]The above formula references the Table named “TableName”, with the special identifier of the header of “Column 3”. This is a single-cell reference. If the header row is showing the result will be the column name or, in this case, “Column 3”. If the header row is not showing the result will be “#REF!”.

This means we can use formulas to tell if a header or total row is visible or not.

Header row visible formula:

=IF(ISERR(TableName[[#Headers],[Column 3]]),"No","Yes")Total row visible formula:

=IF(ISERR(TableName[[#Totals],[Column 3]]),"No","Yes")Another Table part which can possibly not exist is the body. It’s important to note this will not affect formula evaluation, but does have a serious impact in VBA which is covered later in this article.

In Data Validation

Using Tables as a source for an in-cell drop down can simplify your spreadsheets, but Table ranges cannot be referenced directly in the data validation source formula. Instead you must name the range and use that name in the validation formula. To do this, navigate to the FORMULAS tab and click ‘Name Manager’, then click ‘New’.

Since the name of any Table must be unique for the entire workbook, you cannot name a range the same as a Table name. This is why some people either use Hungarian Notation with naming Tables, or preface all Table names with a “t”. For example, if you have a Table with a list of countries, instead of naming the Table “Countries”, you would name it “tCountries”. This way if you wanted to have those countries as a data validation drop-down list, you could name a range of “Countries” which points to the Table range. Here is an example:

Name: “Countries”

Refers to: “=tCountries[Countries]”

In Charts

Putting your data into Tables and using structured referencing makes it easier to create dynamic charts that change as the data in the Table changes. As to not reinvent the wheel, we’ll refer you to Jon Peltier’ great post about this topic Easy Dynamic Charts Using Lists or Tables. The takeaway from the blog post is Tables make great data sources for charts which grow and shrink as the source data set changes. It’s a nice alternative from having to manually create dynamic named ranges.

In Formulas

Putting all of this information into practice can be confusing. Let’s look at some specific structured referencing syntax examples in formulas. Keep in mind that structured references always evaluate to a range of cells and are treated like any other range reference in Excel, so if you’re referencing more than a single cell it must be used as an aggregate, range array, or lookup array, depending on the formula to which they are being passed.

There are five specific locations we can reference:

- Body column

- Entire column

- Column header

- Column total

- Column cell

The examples below assume the Table’s name is “TableName”, using column “Column Name” where applicable.

Specific Column Body or Data Excluding Header and Total Rows

TableName[Column Name]Specific Column Including Header and Total Rows

TableName[[#All],[Column Name]]All Data Excluding Header and Total Rows (Data Body)

TableNameAll Data Including Header and Total Rows

TableName[#All]Row Across All Columns

TableName[@]Row for One Column (Single Cell)

TableName[@[Column Name]]Header Row Across All Columns

TableName[#Headers]Header Row for One Column

TableName[[#Headers],[Column Name]]Total Row Across All Columns

TableName[#Totals]Total Row for One Column

TableName[[#Totals],[Column Name]]Let’s assume we have a column in our Table which is titled “Column 3”. Below are examples of the types of structured references we can use to reference specific parts of that column.

Specific Column Body or Column Data Excluding Header and Total Rows

TableName[Column 3]

Specific Column Including Header and Total Rows

TableName[[#All],[Column 3]]

Header Row for One Column

TableName[[#Headers],[Column 3]]

Total Row for One Column

TableName[[#Totals],[Column 3]]

Row for One Column (Single Column Cell)

TableName[@Column 3]

In VBA

There are two basic methods for referencing Tables and parts of Tables from VBA. The easiest is to use the same syntax as described above for formulas where you pass the Table information as a text string to the Range object. The other method is to use the Excel object models ListObject and its child properties and methods. Both are described below.

Using Range and Evaluate

Just as with standard referencing, the Range object evaluates structured references passed as a text string. For example, to reference the body or data portion of “Column 3” in the Table named “TableName” using the Range method:

Range("TableName[Column 3]")Note that no qualifying worksheet is required because the table name has to be unique across all worksheets. This is the referencing style you will see when using the Macro Recorder.

Using the Object Model’s ListObject

To reference any part of a Table using the Excel object model, we have to first identify the Table object itself. The ListObject object is how Excel exposes a Table in the Excel object model. It is contained in the collection ListObjects which is a child of the Worksheet object. Use this syntax to reference a specific Table on a worksheet:

ThisWorkbook.Worksheets("Sheet1").ListObjects("Table1")ListObjects, being a collection of list objects or Tables, can also be accessed with an index number:

ThisWorkbook.Worksheets("Sheet1").ListObjects(1)The index number of the Table is the order in which it was created on the worksheet and is a read-only property.

Once we have the Table’s ListObject object we can access and manipulate any part of that Table. The more commonly used properties and methods are discussed below. Each example starts with this code:

Dim Table1 As ListObject

Set Table1 = ThisWorkbook.Worksheets("Sheet1").ListObjects("Table1")Range Property

The Range property returns the entire Table as a range object including the header and total rows.

Dim Table1Range As Range

Set Table1Range = Table1.RangeHeaderRowRange Property

The HeaderRowRange returns the Table’s header row as a Range object. The range is always a single row – the header row – and extends over all Table columns. When the header row is not showing this property returns Nothing.

Dim Table1HeaderRowRange As Range

Set Table1HeaderRowRange = Table1.HeaderRowRangeDataBodyRange Property

The DataBodyRange returns the Table’s body as a Range object. The range is every row between the header and the total row and extends over all Table columns.

Dim Table1DataBodyRange As Range

Set Table1DataBodyRange = Table1.DataBodyRangeWhen the Table does not contain any rows the DataBodyRange property returns Nothing. This may be confusing when looking at the worksheet as it will appear as if a single row exists. This is the only case when the property InsertRowRange returns a range which can be used to insert a new row. Effectively InsertRowRange and DataBodyRange are equivalent.

TotalRowRange Property

The TotalRowRange returns the Table’s total row as a Range object. The range is always a single row – the total row – and extends over all Table columns. When the total row is disabled this property returns Nothing.

Dim Table1TotalRowRange As Range

Set Table1TotalRowRange = Table1.TotalRowRangeInsertRowRange Property

The InsertRowRange returns the Table’s current insertion row as a Range object only when the Table DataBodyRange object is Nothing (the Table has no data rows); it’s Nothing when the DataBodyRange is a Range (the Table has one or more data rows). While this range was always the last data row in Excel 2003 (the row with the asterisk), it was partially depreciated in Excel 2007 and remains so in 2013. In Excel 2007 and later versions it only returns the first data row and only when the Table does not contain any data. Otherwise it returns Nothing.

Two additional properties or collections provide access to the rows and columns in the Table. Each collection provides access to all of the ListRow and ListColumn objects in the Table. Each ListRow and each ListColumn object has properties and methods.

ListRows Property

The ListRows property returns a collection of the rows in the Table’s DataBodyRange as a ListRows object type. It behaves very much like a Collection object and contains a collection of all the ListRow objects. Rows are referenced only by a one-based index number relative to the first row. An empty Table has no rows. The ListRows.Add method can be used to insert new rows.

Debug.Print "The Table has " & Table1.ListRows.Count & " rows."ListColumns Property

The ListColumns property returns a collection of the columns in the Table as a ListColumns object. It behaves very much like a Collection object and contains a collection of all the ListColumn objects. Columns are referenced by a one-based index number relative to the first column or the column header. The ListColumns.Add method can be used to insert new columns.

Debug.Print "The Table has " & Table1.ListColumns.Count & " columns."

Erdöl Biramen says

Is there any structured reference to give me the table column name of the currently active table column?

e.g.

table occupies the range A1 to C4

A2 and C2 are the headers (col1. col2, col3)

the active cell is B4

is there a structured reference which would give me the column name “col2” ?

Jon Peltier says

Erdöl –

You need to know what the column headers are. In this way, Tables are designed like database tables, where the field name and not its position are what matters.

Andrew Lister says

Is there a way to make a column of the table reference another row selected dynamically by a value outside the table?

I’m thinking of a column “Current Language” which would consist of a formula something like Tablename[@ cur_Lang] where cur_lang is a named range that contains the result of a user selection from a drop-down list of the other column headers, e.g. English, French, German, etc.

This seems as if it ought to be trivially simple, but every attempt I make ends in a curt error message.

Andrew Lister says

Following on from my previous comment, I succeeded (after a fashion) with this ugly construct as my dynamic column formula: =INDEX(Languages,(ROW(E3)-2),MATCH(cur_Lang,Languages[#Headers],0)) but this is anything but robust—If I relocate the “Languages” table, the row reference fails, and the @ did not work within the Index function.

What is worse, =CHOOSE(1,Languages[my Lang]), where “my Lang” is the name of the column with the above formula abomination only works if it is on the same row as the table, rather defeating the object of the exercise as far as I am concerned.

I have to admit, I am not “feeling the love” for Tables so far! Any pointers very gratefully received!

Jon Peltier says

The structured table referencing works nicely from inside a table. From outside, I rarely use it, unless Excel automatically generates it (which is if I’m referencing data from the same row of the worksheet), or if I’m referencing whole columns of a table.

Tom says

Using Structured Tables/Addresses, how would you address the row below the current row?

=IF(A1=A2,”Yes”,”No”)

=IF([@Column]-????,”Yes”,”No”)

Jon Peltier says

=IF([@Column]=OFFSET([@Column],1,0),”Yes”,”No”)

bobby2007 says

I would like to reference the structured table’s first row after filters.

How do I call for cell that constantly changes after being filtered the structured table?

OUTSIDE OF THE TABLE, non parallel to the table, unable to use this row.

Table Name: TABLE1

Row: 1

Column: Q1

Link Table Rows across Sheets says

I have a very large multidimensional data list (50,000 + lines of MLB batter data with 30+ variables for each line) to represent a specific game date feature vector (e.g., name, team, position, home, away, pitcher, umpire, score, date..etc). The players are sorted alphabetically, and the first record of each hitter is the last date. I would like to perform a moving average on each player for a specific value under various parameters (home, away, right hand pitcher, left hand pitcher, day, night). I have on one sheet, a list of unique hitter names, the number of games, and the relative anchor position for the beginning and ending of each players season record. The first part of my question involves formulas and not VBA. I can do a COUNTIFS, and SUMIFS to identify the number of game types for each hitter. What I need to do is pull out the dates for a specific count (say 5 games). I have a “master” Table that represents master[Date] on a separate sheet (also called master). On another sheet I have the anchor position and final position of the beginning and ending dates (e.g. E2, E160 for the relative positions on the other sheet. I am getting a weird error when I try to reference the beginning date

master[Date](Beginning Row) eg. master[date]E160:E160

Can you shed some light how to reference a specific row (the 160th row) of a Table column from one sheet to a cell value in another Table in another sheet?

I tried the usual Index, Match, Vlookup, Lookup and it gives me the wrong initial date

Thanks

Jon Peltier says

Each record is a game, not an at bat?

To get the first occurrence of a player in a column of player names, where the names are sorted alphabetically and listed multiple times, I would use (pseudocode):

and to get the last occurrence:

If I use

for the first, for some reason it returns the last occurrence, and I would have expected the first. So I used the optional third argument of zero in the Match formula above to get the first occurrence.

Of course, a search of a sorted list is faster than a search in an unsorted list (third argument of MATCH = 0), so it would be faster in a large table to use:

Last occurrence:

First occurrence:

Now I have the index of first and last occurrence of each player in the master table, and I can use these indexes (indices?) to extract other information from the table.

BREMOND Vince says

Hello,

Thanks a lot :)

Suggestion: for the ‘In Data Validation’ section, the uasage of Indirect function is for me more efficient than naming ranges.

I.e =INDIRECT(“TableName[HeaderName]”)

Jon Peltier says

Vince –

That’s interesting, I hadn’t tried INDIRECT for this.

bs0d says

What about referencing a single cell within a table?

Alexander Wolff says

How can I do abs or rel or mixed references to tables (table columns)?

I’d like to copy

=SUMPRODUCT($A1:$A9;B1:B9) to the right, resulting in

=SUMPRODUCT($A1:$A9;C1:C9) and so on.

How to treat table notation likewise? Thank you!

Jon Peltier says

Unfortunately the Table Structured Referencing is only relative. You would have to either modify the first formula to use Standard Referencing ($A1:$A9) or modify the dragged formula to refer back to the original column.

EDIT: Aaron points out that multiple-column references are absolute, while single-column references are relative.

So this:

=SUMPRODUCT(Table2[ColumnA],Table2[ColumnB])

becomes this when dragged to the right:

=SUMPRODUCT(Table2[ColumnB],Table2[ColumnC])

But this:

=SUMPRODUCT(Table2[[ColumnA]:[ColumnA]],Table2[ColumnB])

keeps its absolute reference to ColumnA while letting the relative reference to Column B slide over to column C:

=SUMPRODUCT(Table2[[ColumnA]:[ColumnA]],Table2[ColumnC])

Aaron says

That’s very incorrect. Table Structured Referencing is far more geared towards absolute references than it is to relative references. The only way to make a relative reference is to confine yourself to a single column or use additional functionality like offset, whereas absolute references can be multiple or single column. If you want a single column relative reference then TableName[ColName] works. For a single column absolute reference, you just modify it as follows: TableName[[ColName]:[ColName]]. Multiple column ranges always follow the second patter, and thus are always absolute references.

Jon Peltier says

Hmm, I’m not sure it’s “very” incorrect. There’s no easy visual way to enforce absolute references (like the $ signs in regular cell references), and the column name in a structured reference makes the reference seem absolute, so it’s easy to get stung by a single column structured reference that is actually relative. Thanks for telling us about the multiple-column style references being absolute. I’ve updated my earlier comment to correct my statement.

Aaron says

Fair enough. It probably seems more obvious to me as I’ve used it quite a bit.

Jon Peltier says

Well, everything is easy when you know how. You knew how, and now so do we. That’s the whole point of this blog, is helping people learn how Excel works.

Casey Missal says

This is a very comprehensive and useful reference!

Unfortunately it doesn’t address my current issue. I am attempting to create a dynamic named list that references a filtered table. i.e. have a list dynamically adjust based on the visible rows in a table.

I have seen many ‘close’ solutions on the net, but none specifically address this.

Any Ideas?

adix says

quick info:

the list of characters (which require an additional set of square brackets around) is not complete.

you missed at least

Tilde ( ~ )

Question Mark ( ? )

Exclamation Mark ( ! )

Under Score ( _ )

Gravis ( ` )

Paul Martin says

Hi Jon, thanks for the post. I have a tricky problem, getting 3 sub-totals per row of a table.

* The table column headers are each week for 3 years: Prev, Curr & Next (the latter is a forecast). Each row has units for each week, and at the end of each row (either in the table or not), I would like totals for each of the 3 years side by side for comparison. I have a solution, which I shall add below, but I don’t think it’s optimal, and doesn’t take advantage of Excel table referencing, which I’d like to do, if possible.

* The date range for each year is a named range DatesPrevYr, DatesCurrYr & DatesNextYr. Each is a subset of the table headers.

* User selects a date range (DateFrom & DateTo) in the Curr year, which defines the dynamic range DatesSelectedCurrYr (variable number of columns, 1-52). From this I also get dynamic ranges (same number of columns) called DatesSelectedPrevYr & DatesSelectedNextYr.

* I have written some VBA code that displays the columns selected. So, if the user has selected 2 weeks, say 18-Feb-19 & 25-Feb-19 for the Curr yr, then there will be these and 4 other columns displayed in the table, namely 19-Feb-18 & 26-Feb-18 (Prev yr) and 17-Feb-20 & 24-Feb-20 (Next yr). If the user selects 3 weeks, there will be 9 columns visible, etc.

* At the end of each row, I want 3 more columns that total ONLY the visible selected columns, Total Prev, Total Curr & Total Next.

So my preferred solution is to use Excel’s table structured referencing. Is this possible?

My workaround at present is a little clunky: I have a column of row offsets (offset from the Date column headers). My formulas for each row look like this:

=SUM(OFFSET(DatesSelectedCurrYr, RowOffset, 0, , ShowNumWkCols)), and similar for the other years

My concern is that (1), it has an extra helper column to get the RowOffset, and (2), it’s a large spreadsheet with many calculations that may be overburdened with lots of OFFSETs.

Any suggestions appreciated.

Cheers, Paul

Jon Peltier says

I’m not too familiar with it, but I think you can use the AGGREGATE function to handle this. It allows you to aggregate by different operations (like SUM), and lets you choose between all cells or just the visible cells.

Sandeep says

A great post.

MF says

Hi! Question. Have been researching this for hours but haven’t found the right search terms.

I’m building a report that helps me manage my company’s A/P. I have data that I export from our AP system into excel, and build my report off of that. I have an aging that breaks out all outstanding invoices into age ranges, and further into the approval stage invoices are in. Use this data to follow up on invoice processing.

Now what I want to be able to do is — similarly to what you can do in pivot tables — click the cell that the formula is in and navigate to the specific rows that constitute that formula, instead of manually going into the table and filtering to get those rows that constitute the formula value (using basic sumifs). is there a way to do this with excel tables? let me know if you need more info!!

thanks!!

Jon Peltier says

Matt –

Every row of the table would be called by the SUMIFS function, so the precedents would include the whole table. Only some rows would be included in the sum, and I think you have to filter the table using the same criteria as the SUMIFS use to see which rows they are.