Earlier this month, the New York Times ran a series of articles investigating payoffs by Biotronik, a medical device manufacturer, to doctors at University Medical Center in Las Vegas, leading to Biotronik cornering that hospital’s market of pacemakers and defibrillators. The story in Tipping the Odds for a Maker of Heart Implants was accompanied by a chart (“multimedia presentation”) called A Quick Change in Heart Devices. The New York Times has published at least two follow-up articles, Tipping the Odds for an Implant Maker and Inquiry Into Payments by Device Maker. I’ve reproduced the New York Times graphic below.

New York Times Donut Charts

It’s a series of donut charts showing the market share of Biotronik over the period during which the physicians were hired as consultants. From a market share of zero in 2007, Biotronik zoomed up to 95% in two years, forcing out their main rival Boston Scientific.

I’m not going to analyze the scandal, but I do want to examine the New York Times’ choice of graphics.

We all know the rationale for donut and pie charts: they show proportion of a whole. And as far as they go, each of these charts is reasonable for its purpose, to show the market shares of two or three vendors (treating “other” as a single entity). In all cases one segment of the chart is much larger than the others, and we get a good qualitative sense for the market at each point in time.

If I had seen any of these charts in isolation, I would not have though much of it. However, this visual uses several standalone snapshots to show how the market evolved. We can get a rough qualitative sense of the change from chart to chart, but to show trends it makes more sense to show data in a single chart than in a series of charts.

Line Charts

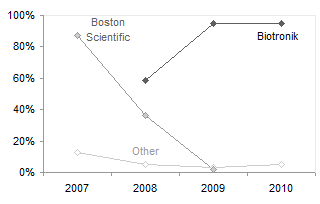

My first cut at the data was with a line chart, market share against year for the three entities.

The lines in these charts draw the eye to the trends from year to year. To further clarify the trends, I decided to replace the blanks in the line chart with zero values, connected by dotted lines to the original values.

This chart clearly shows how rapidly Biotronik grew its market share and how precipitously Boston Scientific’s share fell.

Area Charts

Suppose we still wanted to show a percent of the whole kind of chart, while maintaining the clear trends. I don’t use stacked charts often, but with only a few areas to consider, I thought I’d try a stacked area chart.

That shows the changing market shares pretty well, but an artifact of the stacking order (a danger of using such charts) makes it seem almost as though Boston Scientific is increasing. So I changed the order of the series.

This chart gives a clear sense that Biotronic started from nothing, and expanded rapidly, pushing Boston Scientific off the bottom of the chart.

A Proponent of Donut Charts Chimes In

I first saw the New York Times donuts in Pie Charts and Doughnut Charts – Tension Releived! [sic] on Paresh Shah‘s Visual Quest blog, where he made much of the inherent Gestalt principles of stability and equilibrium in pie and donut charts. Paresh followed up in Gestalt Principles. Doughnut charts.Pies, in which he states that pies and donuts “satisfy the human craving for stability and equilibrium”. Well, I wanted to learn more about the relationship between pie charts and various Gestalt principles, so I Googled pie chart stability equilibrium:

The first two links are to the first article by Paresh cited above, the third is to the web site of a woman whose Balance of Self Theory uses a “Balance Pie Chart” to help maintain one’s stability in life. The fourth links to a comment by Paresh in a recent post of mine, Why Do We Love Pie Charts?. Further down the list is Excel chart gallery: a difficult equilibrium by Jorge Camoes on his Excel Charts blog, where he discusses not Gestalt principles but instead the preponderance of “junk” charts in Excel’s chart types dialogs. In the first five search results pages, I found no mention of the stability and equilibrium of a pie chart.

A follow-up search of pie chart gestalt turned up Paresh’s article cited above, his comment on my post also cited above, and his comment on In Defense of Pie Charts, by Robert Kosara on the Eager Eyes blog. But there is nothing else about stability and equilibrium of a pie chart in the first five search results pages.

So I guess there isn’t a lot of discussion abut pie charts satisfying the human striving for stability and equilibrium. For me, the obsession with clearly presented data completely overwhelms any desire I have to seek stability within circles. A poorly conceived and implemented graphic actually upsets my equilibrium. SteveT commented on my Why Do We Love Pie Charts? post that pies may satisfy not Gestalt, but something Freudian.

Joe Mako says

How about stacked bars:

http://public.tableausoftware.com/views/StackedBars/example

Jon Peltier says

Joe –

I made some stacked bar charts, but I preferred the stacked area charts. With gap width set to zero, as in your example, I thought it looked too blocky or choppy, and with a gap between bars, I though it looked disconnected.

SteveT says

And here I thought my “Freudian” comment went un-noticed. Thanks for the tip of the hat.

I think that Donuts might be even more “Freudian” with the center drawing your attention and a comment from my wife of: “My eyes are up here ;)”

I totally understand that Pie/Donut charts are not good representations of data especially for comparison purposes. However, I actually like the donuts that you reproduced from the article and think that they quickly tell a story that is hard to decern in all the re-attempts. I believe that this is especially true if you presented the Stacked Area vs Donuts to a lay person. I think they would get/understand the donuts more often and more quickly.

Perhaps the happy medium is that Pie/Donuts should be used in rare circumstances, and only when you have less than 4 slices/divisions and only when you are showing an OVERwhelming protion or an OVERwhelming trend. Maybe we should think of Pie/Donuts as the Sparklines of the Area chart.

Paresh says

Hi Jon,

Maybe you should read up on the following article from The Before and After Magazine : Article No. 0676 Gestalt Theory : Equilibrium which incidentally is available on the web – but you will have to make an effort.

The fact that you did not find any direct reference to pie chart and equilibrium only goes to prove that maybe I am the first one to correlate the concept and the chart! You should look up page 2 where there are a few images which portray equilibrium, a lemon wedge [ quite close to a pie chart] , a circle.

I wonder if Now you can see it!!

Joe Mako says

Paresh,

Thank you for pointing out that article. It was a nice easy read. My initial reaction after reading it is, I want my charts to have tension. That when there is equilibrium, things are centered, aligned, and the viewer is relaxed. In a visualization of quantitative data, I am most interested in the values that are not aligned, not equal, that have a difference, I want to see what is of interest quickly. In order to do that I will need to be able to make comparisons of the values. After reading the article, I want tension because it makes it easier for the viewer to see the differences. That with tension, there is a story.

Do you want a equilibrium or tension in your charts? Or am I misunderstanding this concept?

Paresh says

Hey Jon

Let us have a poll on this – it would be fun to find out how may prefer a particular option!!

Paresh says

Hi Joe

Both tension and equilibrium have their place – but having a structure which is in equilibrium makes it easier to concentrate on the content, data in our case.

In the case of the pie charts, the structure is in equilibrium, the tension is in the data – tumultuous change in market share.

Jon Peltier says

I only read page 2, because they want me to purchase the whole PDF of the issue this article appeared in. On page 2 I read that our eye is most comfortable in the center of a circular object, at the point of greatest equilibrium.

Well, aside from the New Age feeling of one-ness this leaves me with (oops, please pardon my psychedelic hippie past), I recognize that the assumption of circular equilibrium is not universal. Not everything is defined as a drop of water.. The greatest equilibrium in a crystalline material is in a faceted solid. In a fibrous material, the equilibrium is also not maximized in a spherical configuration.

Applying this equilibrium explanation to the donut graph, I first notice that the donut charts have an empty center. Whatever, the following argument holds for pies as well, which are round and do have a center. To me, any “equilibrium” would be upset by (a) the different wedges competing for space at the hub of the circle (which after Joe’s comment you admitted is tension), and (b) my eye having to lunge back and forth between the several donuts in the graphic to try to compare values (causing more tension). In fact, the four circles are distracting, because all I can think of is which two should line up with my eyes, like goggles or eyeglasses.

This tension and distraction in the multiple donut graph makes it harder, not easier, to concentrate on the content. It’s not constructive tension.

In the line and area charts I proposed, and even in Joe’s stacked bars, there may not be any Gestalt equilibrium, but there is no destructive tension. A simple look makes it easy to compare values and to actually trace the trends over time. The multiple donuts make this trend more difficult to discern, despite how abrupt is the change being plotted.

Paresh says

Well Jon

Let us agree to disagree on this one.

We need to assimilate ideas from different fields to take this area further, statistics, design………

and yes Jon you have to pay up for things – we do charge for the things we do also, don’t we!!

Jon Peltier says

Yes, good ideas are welcome wherever they come from. I’m just thinking that this equilibrium concept, which is certainly nice for some aspects of design (graphical and otherwise) is impeding the meaningful display of information.

I also don’t mind paying for things I value, but I wasn’t sure about the article you’ve cited. It’s less filling than so much other content which is freely available. I’ve since read the article, and the most useful page is the one showing equilibrium with respect to page layout. The rest seems a bit touchy-feely, and not helpful for graphical displays of data.

Joe Mako says

Here is another viewpoint on design concepts:

http://www.visualmess.com/index.html

The main thing I walk away with is:

That the goal of information design is to make it easier for people to find information.

You can set everything to center, or make it all a round pie/donut chart, and you can call it good enough, and the data is presented, but is it the best way? How can you tell what is a better way to visually present the information?

There is a lot of great content in this article, lots of great questions to think about when designing something that will be communicating information.

I agree with Jon, using a series of donut charts to display something changing over time is not a method that takes into consideration the way people visually process information, it take more conscious effort to parse the series donut charts. It does display the information, but it is not the most effective form.

paresh says

Hi Joe,

Nice note on the design concepts there. I completely agree with the conceptual underpinning of your comments – make it easier for people to find information.

I would have also agreed with you if there had been changes in a number of slices and the changes had been more subtle.

But for the drastic changes shown here – the doughnut charts are effective, equally if not more effective than the examples.

Yes this has been fun – a great debate here.

Jon Peltier says

Paresh –

Even for the case of huge changes, these donut charts are less effective than the line and area charts. Each pie is a discrete entity, and the eye is forced to stop at each one. The information from each chart has to be chunked into short term memory, and stopping at the next donut to absorb its details may cause the earlier chart’s information to be forgotten. A line or area chart is a single entity, with the data tracked within that entity from one state to the other. Much easier for the eye to follow, and the entire behavior fits within one chunk in short term memory..

SteveT says

Jon,

I think you are confusing “effective” with “efficient”.

An efficient machine will get it done using a minimum of power.

An effective machine will get the job done well.

The line and area charts are more efficient, but I would disagree that they are more effective.

Jon Peltier says

Steve –

Semantics, eh? I’d say efficiency is a substantial part of effectiveness.

You think the donuts get the job done well? I don’t agree. It takes more effort on the viewer’s part to decipher the information.

SteveT says

My wife agreed with me, but then again, it wasn’t a sufficient sample size for a final determination.

paresh says

LOL !!!