There is quite a discussion ongoing in Business intelligence vs. infotainment on Nathan Yau’s Flowing Data blog. It all started with a marketing guy from Teradata praising the innovation of the data visualization of David McCandless, designer of The Visual Miscellaneum. Stephen Few responded to Teradata’s praise of McCandless’ work in Teradata, David McCandless, and yet another detour for analytics, in which Few called McCandless to task (again) for passing off ineffective data art as cutting-edge information visualization. Nathan called attention to Stephen’s “rant”, and we were off to the races.

I will let the dozens of comments under Nathan’s post speak to the debate about McCandless’ efforts, which I find eye-catching but generally not effective at sharing actual information. However, I did want to share my thoughts on why so many of us continue to use ineffective visualization techniques.

“People like ineffective graphics”

A number of commenters stated that that people like attractive, sexy-looking presentations and fluffy pictures, regardless of their shortcomings. Andrew Vande Moere of Infosthetics suggests that we try to “learn why people actually prefer the less ‘effective’ infographic” (and he specifically mentioned “circular graphs”), so that we can improve the general state of data presentation.

Few replied, “I’m not aware of any research offhand that specifically attempts to explain why some people (certainly not all) prefer forms of display that don’t effectively provide what they need from the information.”

I have a hypothesis about this, pure speculation really, but others may add to it, or at least be amused.

Why do we love pie charts?

We don’t like ineffective graphics, we like familiar graphics.

We learn pie charts from Miss Jones in second grade. Miss Jones teaches many subjects and has to keep a classroom orderly and well-mannered, so she is by no means an expert in data visualization techniques. However, she is a person of authority and we naturally follow her example.

Over the years, we see many pie charts, taught to every second grader by all the well-meaning Miss Joneses out there. The pies are ubiquitous, so we become familiar with them, and we never realize their limitations.

Since all of out software packages, particularly the expensive shiny ones, offer pie charts prominently, we assume they are among the best charting options.

When we see an icon for a 3D pie chart, we click on it, because after all, it’s one whole D better than 2D.

Pies have been ingrained in our consciousness for so long, they become one of the first things we reach for.

Proof That Circular Graphics Are Not Intuitive

Maybe “proof” is too strong a word, but what follows is certainly a telling demonstration.

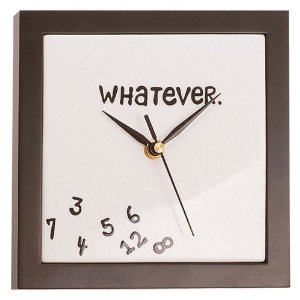

To anyone who doubts how unintuitive circular charts (pies etc.) truly are, I have a simple question: Have you ever taught a young child to read an analog clock?

If children know their numerals, they can read “8:47” on a digital clock, and at least know it’s between 8 and 9 o’clock. In time they even learn that :47 means closer to 9:00 than to 8:00. On an analog clock, 8:47 is obviously closer to the following hour, but knowing the hour isn’t easy. You either have to estimate the angle of the hour hand, or you have to count and interpolate between ticks or read the numerals. Clocks with a square face have lost some of the supposed effectiveness of circular symmetry. And don’t forget the additional difficulty provided by hours expressed in Roman numerals.

Disclosure: The clock images above are affiliate links to product pages on Amazon, where you can purchase such clocks, and earn me a teeny commission. There is a round Whatever clock hanging in the hall outside my office.

A Defense of Pie Charts

I have read Robert Kosara’s recent In Defense of Pie Charts in his Eager Eyes blog. He points out (as Stephen Few did way back in Save the Pies for Dessert (pdf)) that pies have one advantage over other types of graphs: you can readily compare combinations of adjacent wedges. In a pie with four wedges, for example, you can compare A+B to C+D. You can also compare A+D to B+C. However, unless this is planned it is simply the result of an accidental arrangement of the data, since you may in fact be more interested in comparing A+C to B+D.

I’ve always felt that this argument is an afterthought, a rationalization for having used that pie in the first place. If you knew a priori that the comparison of added data points was important, you could easily enough have prepared a stacked bar chart with A+C vs. B+D, or even with all pairs. This would of course be preceded by a bar chart comparing all of the individual points.

Jeff Weir says

Jon: Nice thought piece. Man, the feathers are flying over at FlowingData, aren’t they!

Regarding your thought To anyone who doubts how unintuitive circular charts (pies etc.) truly are, I have a simple question: Have you ever taught a young child to read an analog clock? …I think that’s perhaps that’s not so much proof that circular graphs are not intuitive as it is that cirlucar graphs with a dual axis are not intuitive, given kids are having to conceptualize several different things at once in order to tell the time on an analog clock. e.g. ’30’ can either mean half, or 30, depending on context. To use a different analogy using kids that paints round graphs in a more positive light, I could cut a dessert pie up into 4 slightly different sized pieces, and I know that my Wife and I will always get the smallest ones if we let the kids choose first. The kids do just fine with comparing angles. Granted, they could perhaps more easily judge if the cake was cut into 4 rectangles with equal width but slightly differing length. But the result is the same. (Or it would be if I actually let them choose first).

I like Jorge Cameos’ begrudging acceptance at http://www.excelcharts.com/blog/is-data-visualization-useful/ that If a single chart can save the world, it will not be a Few’s or Tufte’s 100% compliant chart. It will be a glossy Xcelsius pie chart. And I especially like his following line (Wow, that’s depressing…)

Paresh says

The Gestalt principle of equilibrium provides an insight as to why we like pies. Humans seek stability and equilibrium in everything we see. The pie charts provide that and that is why we like them.

[ Refer my post – Gestalt Principles. Doughnut Charts. Pies at http://www.visualquest.in ]

Jan Willem Tulp says

Very good post, might have been a great contribution on the flowindata website itself! :)

Jon Peltier says

Paresh –

You must have clicked on the submit button before entering your information, but I’ve corrected it.

I think this Gestalt stuff can be taken to extremes. My obsession with clearly presented data completely overwhelms any desire I have to seek stability within circles. In fact, a poorly done graphic (like the four donuts you reference from ) is so much worse than a simpler rectangular display, because the use of multiple circular elements obscures trends between the elements. I started on a post about that a couple days ago, I hope to finish it soon.

Mladen Djuricic says

Great reading… I strongly agree with thesis that people use to learn to interpret pie charts because they are so omnipresent. Aside of this, the empirical results show speed and accuracy of estimations in pie charts are not so bad at all. Here is Ian Spence article with some experimental results: http://goo.gl/NOu3g

paresh says

Hi Jon

I look forward to your post regarding a better presentation of the data in the four doughnut charts.

If you look at the doughnut charts, they clearly show the change in dominance fom one company to the other – which is the point of the chart and the investigation. There are no other relevant trends.

In such cases, I do not agree with your view that that this is a ‘poorly designed graphic.’

SteveT says

Perhaps the love of Pies is more Freudian in nature. Their round, they are comforting and you can’t wait to put them in your mouth.

catherine says

I think people like pie charts because they can see what “all” is, and they can see “what part of all” the item of interest is. Pie charts are quite easy to read to get an overall picture of relative proportions when there are only 2 or 3 categories. I’d say they are in fact quite intuitive. But of course when you’re showing 37 categories and they are all about the same size, well, there is just no excuse for that.

Matthew D. Healy says

I don’t use pie charts for reasons Jon has given many many times. But here is one I liked a lot: http://www.chocolate-editions.com/s_pc

Jon Peltier says

Hi Matthew –

I like that one too. I wrote about it back in 3D Pie Charts.

Ed Ferrero says

Hi Jon,

I suspect that pie charts have been somewhat abused over time. I remember first using pie charts in very simple presentations done in the McKinsey style – one slide, one point.

The slides had one sentence at the top, that had one key message, with a chart below it to demonstrate and reinforce the message. Often, that was a pie chart.

An example is “We have about a one-third market share, but we are not the largest player in the market”, with a simple pie chart below it. The next slide would build on the previous point, so that the linked series of slides told a story.

These presentations were all about telling a story and asking business managers to take some particular action. They were not about analysing data, that was all done previously (and we kept senior managers well away from that).

These days people tend to want to use a single pie chart to make far too many points. A series of pie charts; pies within pies; a pie chart with 12 segments – these are all examples of trying to press the humble pie into slots it was never meant to fill.

I still think that pie charts have their place. They are a good tool when used to show a very simple message. Like all charts, they can be used inappropriately.

Jon Peltier says

Paresh –

Without the “www” prefix, the URL for your web page throws an error.