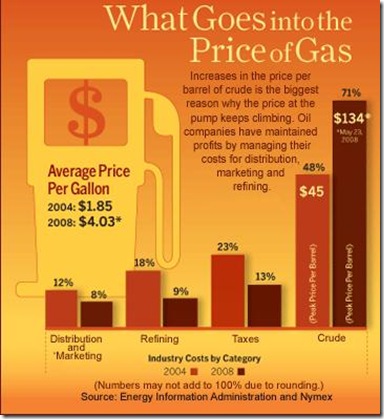

In Data Visualizations Related to Gas Prices, Tony Rose of Support Analytics Consulting shows a series of visualizations he’s culled from the web, all related to gasoline prices. One infographic stuck out, partly for its overuse of chart junk, and partly for Tony’s interpretation. Here is the original chart, which Tony took from www.thebiblog.com, followed by Tony’s comments, which I’ve condensed.

Here is a visual of what makes up the price for gas in 2004, when the average price was $1.85 per gallon versus 2008 where we are now paying roughly $4.03 per gallon on average. . . . One fact that I would have expected to see below is a dramatic increase in the distribution cost of gas between 2004 and 2008, which actually decreased. Seems like there should be an almost perfect correlation between distribution costs and the price of gas, right? Maybe the impact is hidden due to the category being both distribution and marketing.

I guess the chart colors and shading were chosen to remind us how grim the situation is. At first it struck me as odd that distribution costs went down (as it did Tony), but then I noticed that although crude tripled in price, its contribution to the total cost of a gallon of gas only increased by about half. I quickly converted the percentages to actual prices for each component in the price, and the story became more clear. I’ve normalized the 2008 price per gallon to $3.72, not $4.03 as stated in the chart above, to make the crude cost per gallon of gas proportional to the price per barrel of crude.

In 2008, all components except refining have increased in actual dollar contribution. Crude has increased by the greatest amount, but distribution and marketing is the second fastest growing component. The three charts below are (a) my version of the original chart of percentage contribution of the components of gasoline price, (b) my chart of the price contribution of these components, and (c) my chart of the increase in price of the individual components. I used horizontal bar charts so the labeling would work better.

(a) Percentage contribution to the price of a gallon of gasoline

(b) Cost contribution to the price of a gallon of gasoline

(c) Increase in costs of components of gasoline price

One chart doesn’t always tell the whole story, and sometimes the selected chart may not tell it as well as a different chart. If I had to squeeze one chart into the space allotted by my editor, I’d use the middle one, showing true cost inputs, not percentages. The percentage chart downplays the contribution of crude prices, and gives the false impression that all other inputs are decreasing in price.

Colin Banfield says

Very nice analysis. You could probably fit all three charts into the same space as the original junk chart and they’ll still be legible! The value axis isn’t required and if you fit two charts side-by-side, you can use a single category axis. If (b) will have the most emphasis, use the top area for that one and the bottom area for (a) and (c).

Jon Peltier says

Colin –

Good points. I think a good composite would be dividing the chart space into four quarters, two-by-two, putting the cost contribution chart across the top two, to provide adequate resolution in the value axis, and putting the other two into the bottom left and right quadrants, perhaps sharing the category axis.

Colin Banfield says

Jon, my thoughts exactly!

Jon Peltier says

The price of crude is a factor in the cost of gasoline, and for the analysis it is an independent variable. The relationship is simplified, because the cost of the gallon of gas I am currently buying is dependent on the price of the amount of crude that was used to produce the gasoline.

For purposes of political discussions, the price of crude may not be not independent, but that is a different argument. Also notice that I said “cost” of gasoline, not “price”. Production and distribution variations, as well as market and supplier induced supply and demand fluctuations, can also impact day-to-day gasoline prices. Ever notice that the price of gas increases right before Memorial Day (end of May in the US)? This is because the weather is nice and people start taking vacations and driving more.

It’s possible the choice of graphic was influenced to minimize the visual impact of crude price. I couldn’t tell by reading he chain of references which eventually led me to the CIO article Gas Prices: How Oil Companies Use Business Intelligence To Maximize Profits. The article was a bit of fluff extolling the virtues of all the wonderful BI software that’s available. The featured graphic, by the way, is NOT at al related to BI.

Damir Sudarevic says

Well, the implied assumption is that the input value (price of the crude) is independent variable or at least controlled by some random events occurring in another galaxy deep in space. This is not the case; the same people who published the cart are the same ones influencing that input parameter and driving it up as much as they can. That makes their conclusion for the price of gas pure nonsense. Tufte has a whole chapter on graphical integrity and lying with charts.

Gary says

I think the original chart – and the reinterpreted chart (a) – are both misleading, dare I say wrong in approach. I agree that (b) is the single one that shows the most important information. If you wanted to add some chart junk, you could overlay the % change for each of the four components near their bars; e.g., Crude +197%.

If the overall price weren’t changing much, then maybe the relative contributions of different components would be an OK story, maybe less misleading, but even there I’d say chart (b) is going to tell that story as well as chart (a), and provide some additional information to boot.

And in that case, shouldn’t it be a stacked bar, since the components add to 100% and that should be called out?

Jon Peltier says

The problem with stacked charts is that each successive bar on the stack has a different baseline, so it becomes difficult to compare bars within the stack or between stacks. All I should need to do is put a title on the horizontal axis of chart (a) to say “percentage of total gasoline price”.