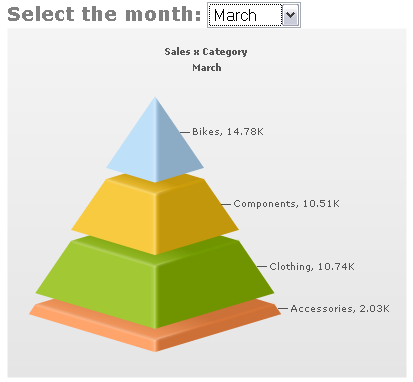

I was directed to the web site for UberBI after reading The Uber Art of Dashboards on the Dashboards by Example blog. I want to say a few words about this chart, a stacked pyramid, which is featured prominently on one of UberBI’s displays.

Stacked Pyramid Chart

I occasionally read the Dashboards by Example blog, although I feel that it lacks any critical assessment of the dashboards it presents. For example, the Dashboard Spy (as the author of Dashboards by Example calls himself) had this to say about UberBI:

“With design deliverables like these examples, they certainly have a grasp of what it takes to design a slick looking dashboard.”

It’s slick looking, all right, if less than efficient and accurate in actually displaying data. One of the commenters added:

“Eye candy is definitely needed on BI dashboard projects whether you like it or not. […] I know you will argue, but believe me that the average user will not care if the blocks are not accurate to their values.”

Wow, it’s hard to argue with such a knowledgeable and outspoken consumer of business graphics. I was going to do a counter-review of UberBI, because I felt it was exclusively an exercise in high fructose eye candy. But I decided a discussion of the above stacked pyramid chart would be a better use of my time.

Let’s take a look at the chart. Looks nice, only four data points, so it’s not too cluttered. The colors are nice too, so I’ll borrow them for my examples. There’s a thin but wide orange (peach?) layer at the bottom, a thick green layer above that, a smaller yellow layer above that, and a relatively small blue cap. It’s nice enough until you study the numbers in the data labels. The small blue cap is the largest value in the pile, and the two mismatched chunks in the middle are nearly equal in value, despite the yellow piece being apparently much smaller.

Although the most obvious dimensional property of each block of the pyramid is its apparent volume, the value conveyed by each block is its thickness, regardless of its area in the other two dimensions. The thickness isn’t even very effective at conveying value: no matter how much I stare at the blue piece on top, it appears as thick as the two middle blocks. If I print out the chart and measure the dimensions of the segments, I can verify that the thickness does scale with the value. But visually it is impossible to see. Even if I flatten the pyramid into a 2D view, the area of each section overwhelms the perception of its thickness.

“Flat” Stacked Pyramid Chart

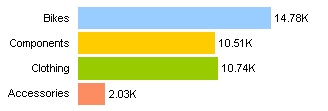

A stacked column chart improves on the pyramid, because the widths of all sections are the same, and the area of each section is directly proportional to its thickness. The blue “Bikes” series is obviously the largest. Stacking the columns this way makes it hard to compare similar values, but clustering them side by side in a column or a bar chart makes all comparisons easy. Use a horizontal orientation to keep labels horizontal (easier to read).

Stacked Column (left) and Clustered Bar (right) Charts

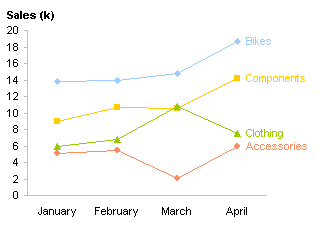

Another problem with many “dashboard” graphics, including the UberBI stacked pyramid and the many dials that grace the UberBI dashboard, is that they only show one point in time. The pyramid allows you to view a selected month, but you cannot see them all at once and cannot assess any trends in the values.

Below is a single chart which requires less space than the stacked pyramid, yet shows data for an arbitrary number of periods. Nothing fancy, no scrumptious eye candy, no sexy 3D effects, just the data. Hey, it’s a line chart! Anyone can make a line chart, even if they don’t have a fancy BI graphics package.

Boring Old Line Chart

The line chart has several advantages over the pyramid chart. First, it shows data magnitudes clearly: values are encoded by a data point’s position along an axis, not by a difficult judgment of the point’s thickness, area, or volume. Second, it shows the trends of the values over time in a single view, without having to switch from one time period to another. Third, it’s clean and fits into a smaller space than the pyramid chart, with no loss of detail.

dermot says

You tell them, John. That pyramid is awful by any standards.

Peder Schmedling says

One time, one of our seniors referred to using a pyramid chart as the same thing as “tampering with the data”.

“The only time you should use this” he said, “is when you need to camouflage large expenses to the management”.

I think that pretty much sums it all up :-)

Thanks for the great blog JP, I’m eagerly reading all your posts.

tb says

Now don’t be too harsh on them.

This kind of 3D piramid graph can be very useful is a sales brochure where you rather want to dazzle the reader than to pass on information.

oh, or did this come from a sales pitch for the dashboard software?

mr tom says

Agreed. Total poo.

They do have a talent for making things look nice, and if they could combine that with telling (from a data perspective) the truth, then they could be a good bet.

As is, though, terrible.

Jon Peltier says

What’s the point of making it look good, if it doesn’t look right?

The pyramid was shown in a demo of the company’s CORPORATE dashboarding software. I guess those corporate underlings really need to dazzle their CEO and shareholders.

mr tom says

“What’s the point of making it look good, if it doesn’t look right?”

My point exactly. They have a talent for the one, but not a clue with the other. If they can do both well, then they can really add value, but otherwise it just isn’t good.

Matthew Pfluger says

mr tom,

Your addition to Jon’s comments on the enterprise-dashboard site was spot on. In these days of “value added” everything, I am surprised that those who claim to know exactly what the C-level “average users” want would choose to ignore this buzzword.

Another point I’d like to make is the lack of keys. I personally don’t mind the dial indicators, but they are useless without a clearly defined key. What does red mean? Similarly, the shaded map of Canada is terrific, but what do the colors mean?

I love an intelligent and useful dashbord, and I’d like to use them more often myself – in engineering design space and system performance evaluations. Overall, I like the dashboard examples. No one argues the need to make dashboards look great, but they must accurately represent the underlying data.

Jon Peltier says

The problem with a dial is that it provides one measurement. This is fine if you’re driving, you need to see how much gas is in the tank right now, how fast you’re going right now.

If you’re running a business, and not pretending to pilot your fancy mahogany desk across your office suite, you need to know what revenues are now, and last month, and the few months prior to that, and maybe you need projections for the following few months a well.

One measurement doesn’t cut it. In a smaller space than most gauges are allocated, you can fit one or more line charts, and present a much more complete picture.

I like looking at dashboard examples, myself. Unfortunately I see too many examples like the one featured here that have severe shortcomings.

mr tom says

Agreed.

I can see the attraction in a dial – it’s really clear (or it is if it’s any good!)whether it is a good thing or a bad thing.

It is an appalling device for a data rich environment such as a dashboard, but for some reason people love it nonetheless.

I think there’s more to it than aesthetics. I think the simplicity also appeals.

I used to believe that only really smart people made it to the top level of most businesses, however the truth is a little different to that!

And there perhaps is the reason for the popularity of dials. Anybody can understand them, even business leaders.

Jon Peltier says

Mr Tom –

You last two lines made me laugh. At first I was going to ask if you’ve ever read Dilbert. But then I saw that you understand.

Before I stopped making such charts, I did a project for a company that consisted of an array of charts, perhaps 18 or 24 in a single screen. The version for the engineers and finance people had an array of line/area charts, while the version for the pointy-haired “leaders” was the same number of dials.

I wonder if they pretended they were playing Flight Simulator. I played that once, about in 1994, and crashed my fighter into the side of the carrier. Oops!

mr tom says

Jon,

Hilarious.

I get my daily Dilbert via RSS, my DNRC newsletter and also read the Dilbert blog (and occasionally comment under this name!)

There’s one other factor we’ve actually not mentioned. Sometimes our great leaders WANT the dashboard to mislead. Especially if it is for an external audience.

Jon Peltier says

“Sometimes our great leaders WANT the dashboard to mislead.”

This is very true. It’s the reason I initially started pasting copies of my charts into PowerPoint slides, so they could not be manipulated. Not that I thought my fearless leaders would intelligently manipulate the data, more that I wa afraid they’d bungle it and I’d look foolish. It was later that I realized the smaller file sizes and improved security that results.

mr tom says

Yeah. I pdf for the same reason.

Plus I have one of the only copies of Bonavista Microcharts in the company ;)

Rod McInnis says

Speedometers in automobiles tell you a lot more than how fast you are going. The reason that all cars use dials is that they allow the driver to see the rate of change in addition to its current value. Speedometers don’t just tell you how fast you are going but also tell you how rapidly that speed it changing. By looking at a tachometer you can see how quickly you are approaching the redline so you can time your shift appropriately. Back in the 80s a lot of sports cars showed up with digital displays that looked really cool but were a big step backwards for data visualization in that application.

Like everyone agrees, dials don’t do a good job at presenting business information because it does not change rapidly while you are look at the gauge. For rapidly changing data that you need immediate information on both the value and the direction/rate of change, dials make a very useful and elegant chart.

I have been coming to this site and directing others to peltiertech.com for years now. The bolg is a great addition to give me a reason to stop in more frequently. Good work!

Matthew Pfluger says

mr tom,

What has been your experience been with MicroCharts? I just discovered them while reading posts on this topic, and I am thoroughly impressed. So are the managers and bean counters at work, and they are interested in learning more. Could you offer some perspecitve?

Thanks,

Matthew Pfluger

Matthew Pfluger says

Rod, I respectfully disagree. In my opinion, dials only show an instantaneous reading of a value. Dials do a poor job of showing rate of change unless you either constantly refresh data or watch for a long time, something people are unlikely to do with Excel dashboards.

For example, the auto shop guys that I know install dial gauges not to see rate of change but quickly see the current value; engine RPM, how close to Red Line, road speed, etc. Other graphs (lines) are better suited for rate of change. However, when I only need an instantaneous value in relation to a min and max, I have no issue with dial graphs.

Jon Peltier says

To some extent I agree with Rod. To the extent that the dial is moving rapidly enough that you can sense its rate of change, then the dial provides that feedback. As Rod points out, this is useful in a motor vehicle, since you can watch the RPM ramp up over the course of half a second or even a few seconds.

But dials in dashboards are not updated at the frequency of the tachometer in your car. I think Rod and Matthew are both saying this. Thus you need a different display approach that shows current and historical values. A line chart satisfies this approach.

If you only need to show an instantaneous value, Stephen Few’s bullet chart is much more efficient in terms of space. You could fit at least three or four bullet graphs in the space of a single gauge. The bullet graph is described here: http://www.perceptualedge.com/articles/misc/Bullet_Graph_Design_Spec.pdf, and Charley Kyd’s Excel implementation is here: http://www.exceluser.com/explore/bullet.htm.

mr tom says

Hi Matthew.

I’m a recent convert to microcharts.

It has some bugs and some annoyances. It takes a bit of getting used to.

But I love it.

It lets me do stuff that excel simply doesn’t otherwise do.

Well worth the investment, and there’s a limited time demo you can use to convince yourself.

Damir says

I guess the only worse one– or equally bad–is the funnel chart. Here are the two showing the same data-set: http://www.damirsystems.com/?p=99

Jon Peltier says

Oh, that’s nasty. I guess it plots by thickness, too, like the pyramid.

I’ve seen funnel charts which were supposed to indicate a process of filtering out items, so each stage of the funnel is supposed to contain fewer items. This would be good, for example, for tracking the success of development projects, where you might start with 100 projects, 90 pass through the initial feasibility stage, 75 pass preliminary design, 50 go on to detail design, 25 pass technical review, and 10 are released to manufacturing.

However, I think that a column or bar chart best illustrates a filtering process at work. The funnel analogy is lacking, because it seems to me that everything squeezes through the entire ever-diminishing cross section of a funnel. Pressure and friction increase, and nothing is really filtered out. And if you get an artistic graphic designer drawing the funnel from a 3D perspective, I don’t know what it looks like.

Damir says

One could simply rotate the bar-chat around the category axis to get truncated-conical shape which can then be used as a funnel or pyramid chart. In this case the width of a disc-element would be proportional to the category value. Why do they do thickness is beyond me.

Jon Peltier says

I suspect they use thickness because (a) the algorithms are easier to implement, and (b) they haven’t even thought of using a different apparent ‘size’ property of the sections. probably a good thing, because these can be improved on only by using a uniform section, viewing the section as a 2D shape, and unstacking the sections.

mermaldad says

To me, the purpose of a stacked pyramid is to express a relationship between the layers. The lowest layer is the foundation upon which higher layers depend. As you noted, the eye naturally sees the volume of each layer as indicating the magnitude of whatever is being measured. A reasonably good example of this is the USDA food pyramid, where the volume (or area) of the layer indicates how many servings of each group one should eat. Moreover, if the because the eye is only so-so at comparing the volumes of the layers, the pyramid is best used when the numbers aren’t the main point.

The chart above ignores all of this. It’s not that the stacked pyramid is bad, just that it is easily mis-used.

Neil says

I agree with all of your comments, I want it to be accurate as well as nice looking. However, in the case of the dashboard I am developing, a pyramid is the recognised way of representing the data theoretically, see below link:

This shows H.W. Heinrich’s Safety Pyramid which proposes that minimizing near misses reduces occurrence of major injuries. Therefore I would really like to show this triangle with real data for all of our offices using a stacked pyramid chart that is not misleading. Ideally I don’t want it 3d, just a flat view like yours above but which represents the data as areas not heights and turns it into a stacked pyramid. Is this even possible in Excel?

I would be grateful for any help with creating this. Alternatively I will just produce it as a stacked bar but this isn’t as asthetically pleasing than displaying it as a pyramid.

Cheers

Neil

Jon Peltier says

Neil –

Yeah, it’s possible, but it’s not straightforward, and I don’t want to encourage sharts that I don’t think are effective.

XLCalibre says

I agree that the line chart is the clearest in this case.

The clustered bar chart (centred on the y axis in my example) is useful in other circumstances though, for example viewing the relative populations at different levels of a heirarchy:

http://xlcalibre.com/hr-dashboard-organisation-heirarchy-pyramid-chart/

Jon Peltier says

The line chart has the benefit of easily and clearly showing how each of the would-be bars changes over time. However, for a single time point and for sorted data, a bar chart is also a good choice.

Centering bars as you have done is an aesthetic treatment which does not help clarify the data. If you were portraying actual detailed values, lacking a common baseline clouds analysis of the bars, and a better choice would be uncentered bars starting from an axis at the edge of the chart.

XLCalibre says

I had a feeling you might say that, and I would tend to agree, though sometimes a client will insist upon a compromise for aesthetics in spite of any protestations you may have. I suppose at least the area is accurate and representative of the data unlike the example that you criticise in this post.

Anonymous says

Since the fundamentals to your article is started by the deconstruction of stacked Pyramid Plot, I would take a moment to put forward a point: “the value conveyed by each block is its thickness, regardless of its area in the other two dimensions.”

Can you cite this from somewhere? The essence of pyramid is the total area and as such the one sitting on top will have a greater thickness manifest than the one below it. This is somewhat analogous to funnel too. Picture leads generated from various entry-points in ones website. The leads generated on the last level could imply a greater impact on sale susceptibility of the lead than the one from the first entry-point.

Jon Peltier says

Based on measurements I made of the sections of the displayed pyramid, the values in the labels were used to determine the thicknesses of the sections. Of course, this is misleading: the volume of each section should be used to represent its value (not area as you stated). But 3-D metaphors like pyramids and funnels will always be misleading when used in a 2-D representation. In face, the usual 2-D representation of a funnel is also usually misleading; the area is not a linear function of distance along the funnel, but length is usually the parameter which is used to encode values. I also don’t like the “funnel” metaphor, because in all of the physical funnels I’ve ever seen, everything that goes in at the top comes out the bottom. Unfortunately, it’s not so easy to represent a “filter” or “screen” metaphor, where some of the contents are stopped at each step.

Anonymous says

3D is charts is always Bad Practice